Eddie Huang does not want to be a poster boy for the American Dream.

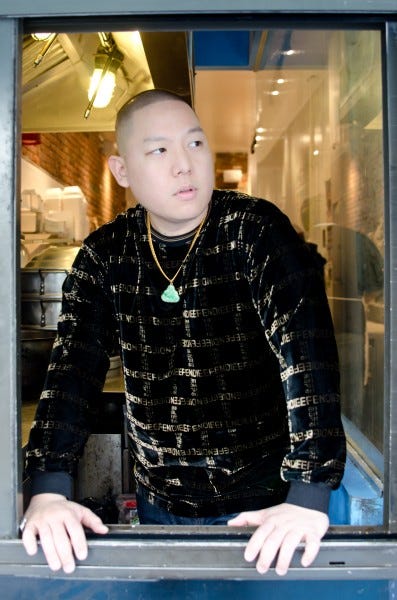

The 30-year-old food celebrity definitely has the rags-to-riches resume. Born in the Washington, D.C., suburbs to Taiwanese immigrants, Huang grew up in his family’s furniture stores and then in their Orlando, Fla., restaurants. He failed. A lot. He failed at school. He failed as a lawyer. He tried stand-up comedy before becoming one of those New York sensations, a brash, hip-hop-talking homie with a late-night eats place who has been called the new Anthony Bourdain. His East Village bun shop, BaoHaus, serves stuffed Taiwanese dumplings to a cult following, but the six-seat joint is less a restaurant than a platform for Huang’s views about the ability of food to change the way we think.

Julia Child’s epiphany came over sole meunière. Huang’s came over a bowl of noodles. And though it’s an unlikely comparison, the sensibilities are the same. “It was one of those bites that makes you think maybe, just maybe, your taste buds carry a cognitive key that can open something in your mind,” Huang writes in his memoir “Fresh off the Boat” (Spiegel & Grau), hitting bookstores this week. “It was then and there that I realized you can tell a story without words, just soup.”

The story Huang tells isn’t about America’s misty-eyed magic. It’s about the hardships the place throws in a newcomer’s way, forcing him to man up and deliver. And like Child, Huang is on a mission to change the way we think about food in America – so-called “ethnic” food: what it means, why it’s important, what it can do, and to whom it belongs. He talked with AFR’s Michele Kayal.

American Food Roots: You open the book with food: your mom and grandpa trying to figure out what’s wrong with the soup dumplings. Why is food so central to the immigrant experience?

Eddie Huang: It’s the easiest way to remind you where you’re from. It’s an activity that brings you back home. There’s a lot of community building you can do, but food is the equalizer. Not everyone plays basketball, not everyone karaokes, but everyone eats food. In communities, there are staple foods and they’re what everyone rallies behind. It brings people together regardless of what you’re into.

And when you live in a country where you’re not the dominant culture -- in New York, I feel great. When I’m outside New York, it’s made very clear to me that this is not my country. To live in a place and think ‘This is my home, but no one else thinks it’s my home’ -- it’s unique to America that so many people are here, some because of political or historical displacement. There isn’t much to be proud of a lot of the time.

Very rarely do minority cultures get to shine. What did we get recognized for this year – Gangnam style? Jeremy Lin? And Jason Wu designing Michelle Obama’s dresses. That’s very, very big. That’s something that I think is very, very cool.

In terms of food, though, that’s a thing on a daily basis that people can point to and say, "That’s my connection to Chinese culture or Taiwanese culture." I feel like at least with Chinese food, people know Chinese food. That’s one of the things we’re proud of.

AFR: You make bao, Taiwanese steamed dumplings. But the restaurant is really more of a take-out joint, a tiny six-seat place. Why do it this way?

EH: Like a lot of good things that are very grass roots and proletariat, it was necessity. I didn’t have any money. We opened and I had $200 to my name. This was the biggest space I could afford. I had horrible credit. We had an aunt put $40,000 in a bank account to show that I had money in the bank, and then she took it out.

Sometimes the universe gives you these challenges because they know you’ll dig your way out of it. And once we did it, I knew that that’s what I wanted to do. It’s not my style to do service and seating and waiters, that’s not how I like to eat. I like to go to a counter, I like the music to be loud, I like it to be a bomb shelter.

AFR: It reminds me a little of your grandparents selling mantou on the street in Taipei. It’s kind of ironic that you’ve repeated that model here in the U.S. What’s the difference between what they did in Taipei and what you’re doing here?

EH: Definitely. The difference is that they – it’s a different food item. It’s the same dough. [Mantou] is like the Chinese bagel. In mine there’s more filling, more meat. We can afford more animal protein in this generation. They would use pork floss, little bits of meat. But the spirit of it is very similar.

That’s the story of my family. That’s the story of a lot of Taiwanese and Chinese immigrants when people are like ‘Stand behind the stove.’ We’re immigrants trying to make our way here. I saw how hard my dad worked in a restaurant. But I want to write a book, I want to host a show. I will never let America keep me in a 400-square-foot box.

AFR: Do you think America wants to keep you in a 400-square-foot box?

EH: I think people on food blogs do. In general, there’s a sentiment that chefs should be in the kitchen.

AFR: There’s a great moment in the book where you turn the tables on “ethnic food.” You’re sleeping over at a friend’s, your first sleepover and your first meal at a white person’s house, and you gag on the tuna fish and the macaroni and cheese. How does the eater’s perspective affect what’s considered ethnic?

EH: It’s entirely the eater’s perspective. I used that passage on purpose to turn the tables. This is what it’s like for me. I never saw myself as below people. America is the one that sees me as different or ‘the other.’ But I’m not different. I used that passage to turn the tables on white people, and say this is how your food would be viewed if you didn’t win those wars.

AFR: We always like to tell a happy story of coming to America and living the dream, but you talk about the real hardship of it, the people who treated you badly because you were different. In the book, you say, “Take the things from America that speak to you.” Is there a myth to the melting pot? And if so, what is it?

EH: The myth of the melting pot? I had a professor who was super important to me. Dr. Jennifer Henton. She taught me not to “suture” things. It’s the literary criticism term for sewing things up in a nice bow. A lot of Hollywood films employ suture. One of the great films I’ve seen is “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” Even though there’s a little suture, it’s very defiant. I want to talk about everything that’s ugly.

My thing is that I definitely didn’t want people to feel like this story could only happen in America. No, this story happened because I was stuck in America. I was here and I had to really overcome a lot of the obstacles America threw my way. Am I happy? Yes. Would I be a different person if I’d been born in China or Taiwan? Yes. I thank America for revealing itself to me and revealing humanity to me. But the book would not be real if I did not expose all these things.

I took what made sense to me. I took what I wanted from America. I didn’t let it sell me a bill of goods. I refused acceptance of a lot of packages, and took the ones I wanted and sold them back to it. It’s very clear that this is not a feel-good American story. It’s a feel-good story about one person and one family that has overcome country, race and in many ways, identity, to be himself.

AFR: Is there any part of the American dream you buy or feel part of?

EH: I do think that America is an interesting place. When the scandals do come around, the people know right from wrong. I think my generation is interesting and I like it a lot. But what people need to realize about America is that every generation has its fight. Because of the Internet and the thought and ability of people to communicate among themselves, we’ve become more enlightened. The more people have the ability to debate freely, you’ll come to better consensus.

There are multiple ways that America insidiously erodes the freedoms we’re supposed to have. It’s every generation’s duty to identify it. Because they’re getting smarter and smarter about how to do it.

AFR: You’re a revolutionary.

EH: I wish.

AFR: You’ve sometimes been on ethnic chefs for corrupting their food. And sometimes on white chefs for doing ethnic food. What does it mean to be authentic?

EH: To me, it’s not about how the food tastes. That’s a very chowhound.com conversation. My thing is about economics. If someone’s going to profit off this culture, it should be the people who brought it.

You’re really taking somebody else’s art form, bastardizing it and putting it in a form for others to consume. Most people in the food industry are just too basic to understand that, because they’re so obsessed with the taste. It’s just funny that they look at food in this vacuum.

Food is art. The place that considers food in the best way is the New York Times. They put it in the Style Section. No one should forget the importance of culture. If it were just about buying and treating and shelling it out, it should be in the classifieds. There’s political and social importance to food. You’re not experiencing it in its glory if you’re not seeing that.

AFR: Can you really be authentic (in an ethnic sense) and be American? How does that work? And how is it expressed in our food?

EH: I don’t really care about authentic. For instance, Andy Ricker is the best example. He’s a white guy who went to Thailand. But he’s making food that’s authentic – he’s learning from people in Thailand. He’s a disciple. He’s an interesting study. Andy has done a good job of introducing people to Thai food in a setting that seems very much like a Thai street stall. He’s very vigorous with trying to maintain the flavors that he experienced, and he gives all credit and respect back to Thailand. He names people on the menu. I don’t think he’s giving anyone money from it, but he goes as far as you can go as a white person doing a restaurant and giving credit to where it’s from.

I would never want to be the person to tell white people. "You can’t cook this." It’s not about, "You’re white and you can’t cook it." It’s about power. There’s very few things that someone from Thailand can bring to America and get people to pay top dollar for. Food is one of them. And when somebody else does it instead, it’s like, ‘There goes our opportunity."

AFR: So if not “authenticity,” what would you call it, what’s important?

EH: I’m concerned about cultural appropriation. Ownership of soft power. Times are changing. People don’t want to fight wars. And food is part of that, part of soft power. People need to be more defensive about it, and they need to take ownership of it. I‘ve been saying forever: Boycott McDonald’s for a day and watch what happens. They have so much overhead and labor and you could do a lot of damage and force them to change the food system. Politically, people just need to be smart and vote with their money.

AFR: Where do you see ethnic food going in America?

EH: We could go the way of PF Chang. You see a lot of these suburbs with, like, dominant culture making fusion food in strip malls. Or people could have a lot more integrity. And I would say that I wouldn’t blame the dominant-culture chefs. I don’t think they have bad intentions. I think minorities in this country, people of color, need to take responsibility and say, "I need to invest in my culture, my community, and my people and go open this business, open this restaurant." We need to take ownership of it.

I’m not talking about the food. I’m talking about the culture and the identity. My restaurant was very defiant. I risked my reputation, my money, and feel I have the right to speak about this. I gave up a lot of things to talk about this issue. I would encourage other people to participate in the battle over soft power.

And the thing is, it’s going to be better for America. And if one day Chinese culture got too dominant in America, I guarantee you I will be on the other side, fighting against it.